Label Text

Published References"John and Mary Pappajohn Sculpture Park", Lea Rosson DeLong, ed., Des Moines Art Center, Des Moines, Iowa, 1923, pp. 38-39

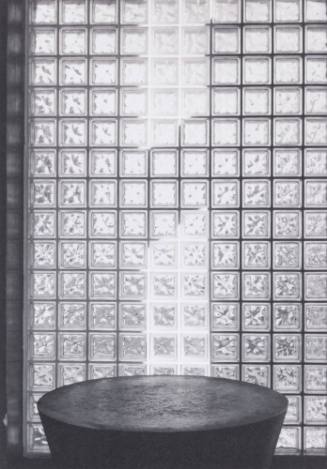

Visitors can sit in Burton’s blocky stone seats and chatting around his tables—such use is an essential element of the artist’s intention. Both sculpture and furniture (or something in between), these pieces challenge and circumvent the boundaries of artistic categories. The artist’s functional works are a response to 1960s Minimalism, a style of abstract sculpture in which the meaning of the sculpture is the viewer’s experience of how the work occupies space. They are pivotal examples of Burton’s aim to draw out the corporeal qualities of abstract sculpture, centering the importance of the viewer’s body and raising the possibility of relating to an abstract sculpture as one might relate to another person. As furniture, and especially public artworks, these objects exemplify the artist’s interest in blurring the distinction between sculpture (high art) and furniture building (craft) as a metaphor for understanding queer experience. Burton speaks on this implicit queer subversion in an early interview with The Advocate magazine conducted in 1981. After commenting how “feminism [of the 1970s] has been a wonderful influence on the art world,” he concluded that “this has been the climate of freedom which has enabled me to come out in a sexual way a little bit more in my work.” (1)

Through his relationship with New York School painter John Button, who Burton dated for ten years, he was introduced to major figures like artist Alex Katz, choreographer Jerome Robbins, and New York City Ballet founder Lincoln Kirstein. He worked as an art critic, reviewing pieces by Minimal sculptors including Tony Smith, and became an advocate for, and creator of, performance art, a genre in which the body itself serves as an artistic medium. Speaking about his sculpture, Burton explained: “Any chair is useful, but a striking, unusual looking chair can make people more democratic about what a chair is. In flexing their attitudes, they may become more democratic about what a person is. Art can be a moral example.” (2)

(1) Edward de Celle and Mark Thompson, “Conceptual Artist Scott Burton: Performance as Sculpture: Homocentric Art as Moral Proposition,” The Advocate, January 22, 1981, T8.

(2)The Advocate, T10.

Published References"John and Mary Pappajohn Sculpture Park", Lea Rosson DeLong, ed., Des Moines Art Center, Des Moines, Iowa, 1923, pp. 38-39

DimensionsOverall: 28 × 22 × 22 in. (71.1 × 55.9 × 55.9 cm)

Accession Number 2015.5

Classificationssculpture

CopyrightARS

ProvenanceMax Protetch; John and Mary Pappajohn [purchased from previous, 1992]; Des Moines Art Center [gift from previous, 2015]