Label Text

Published References"John and Mary Pappajohn Sculpture Park", Lea Rosson DeLong, ed., Des Moines Art Center, Des Moines, Iowa, 1923, pp. 54-55, details pp. 10, 56, 57

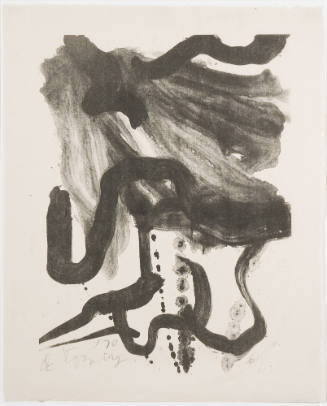

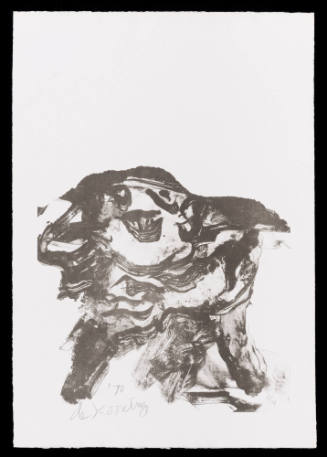

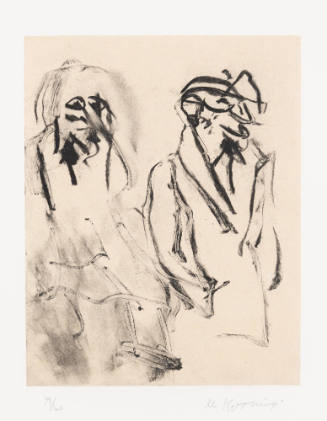

During a 1969 trip to Rome, renowned Abstract Expressionist painter Willem de Kooning ran into an old friend, the American sculptor Herzl Emanuel. He invited de Kooning to visit his studio, and, at Emanuel’s urging, the 65 year old de Kooning tried his hand at sculpture for the first time, manipulating clay with his eyes closed. He created thirteen sculptures that were then cast in bronze by Emanuel. Not long after, British sculptor Henry Moore saw these small experimental works and encouraged de Kooning to explore the forms on a larger scale. De Kooning began making life-size sculptures in the 1970s and then, working at a monumental scale in 1980. The artist made about two dozen sculptures during his lifetime, and these works were strongly shaped by his approach to painting rather than an exploration of the history and techniques of sculpture. De Kooning’s bold, sweeping gestures in clay closely evoke the expressive use of paint within his practice. “In some ways,” de Kooning declared, “clay is even better than oil. You can work and work on a painting but you can’t start over again with the canvas like it was before you put the first stroke down....But with clay... if I don’t like what I did, or I changed my mind, I can break it down and start over. It’s always fresh.”(1)

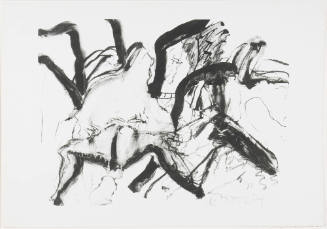

Additionally, de Kooning carried over his long-time interest in the female form from painting to sculpture. He is perhaps best known for a group of paintings he started in the 1950s called the Woman series. These nearly abstract though still recognizable images of women emerged from a long tradition of male Modern artists (including Édouard Manet, Paul Gauguin, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso) who depicted and deconstructed the female body to explore questions about color, form, and the genre of the female nude. As in the Woman paintings, Reclining Figure might seem an abstract sculpture at first glance. With closer examination, the bronze form resembles a woman propped up on one arm with her leg stretched high in the air. Scholars have noted the sense of violence in de Kooning’s deconstruction of female forms in both painting and sculpture, with one describing his sculptures as created “with merciless fingers — more cruel than any brushstroke or slash of a knife because more direct.”(2)

(1) Peter Schjeldahl, “de Kooning’s Sculpture So Far,” in De Kooning: paintings, drawings, sculpture, 1967–1975 (West Palm Beach: Norton Gallery of Art, 1975), 14.

(2) Claire Stoullig, “The Sculpture of Willem de Kooning,” in Willem de Kooning: Drawings, Paintings, Sculpture (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1983), 241.

Published References"John and Mary Pappajohn Sculpture Park", Lea Rosson DeLong, ed., Des Moines Art Center, Des Moines, Iowa, 1923, pp. 54-55, details pp. 10, 56, 57

DimensionsOverall: 68 × 140 × 96 in., 4000 lb. (172.7 × 355.6 × 243.8 cm, 1814.4 kg.)

Accession Number 2015.11

Classificationssculpture

CopyrightARS

Signedde Kooning sc.

Inscriptions1969-83

3/7

Edition3/7

Provenance(Matthew Marks Gallery); John and Mary Pappajohn [purchased from previous, 2002]; Des Moines Art Center [gift from previous, 2015]